Phil’s Blog

Well, we did it, we reached the Big Apple in one piece… sort of. My faithful Mach 40 Imerys and I raced a total of 3798nm from Plymouth to New York. The last few weeks have been a whirlwind of a journey to hell and back. The weather gods turned particularly aggressive and really did everything possible to stop us reaching New York. Out there in the hostile North Atlantic we faced some horrendous conditions that were without doubt the toughest of my sailing career. Nothing could have prepared us for how much of a relentless kicking we would actually get throughout this race.

The first major hurdle the Class 40 fleet had to encounter was a mid-Atlantic low after just a few days of racing. This was only forecast to be small when we set off, but it quickly deepened into a serious depression and was set to consume nearly the entire North Atlantic. There was no way around, we had no choice but to go straight through the eye of the storm and then reach through one of the windiest sectors offering a sustained 40 to 50 knots, gusting 60. The power of this was quite incredible. Once the storm hit, I hoisted my storm jib, a little bigger than a pocket handkerchief, and within 30 seconds I was launched down a wave to hit 24 knots on the log. The night continued like this over and over again – it was a nightmare roller coaster. I was very anxious about the integrity of the boat throughout this time, concerned it would get damaged crashing off waves at such speed. At one point I actually tried to slow the boat down by dragging ropes out of the back… the change wasn’t particularly noticeable!

Imerys pulled through the storm like a hardened polar bear breaking through an arctic winter! but now with a 20 mile lead, I was kindly notified by the race organisers that I had been awarded a six hour stop-go penalty… I had accidentally cut the corner of a traffic separation zone on the first night of the race, hammer. It was out of bounds unbeknown to me and my “detailed race briefing”. Six hours! I couldn’t believe it, I was raging. Everyone knows that skipper briefings exist because no one reads their race instructions thoroughly, and I was no exception – apart from the fact I had to miss the pre-race briefing in order to collect my US visa in London, but it wasn’t all bad luck.

As it turned out, the penalty had its benefits. Exhausted, I made use of what turned out to be a valuable six hours as I found my rudder fittings had worked loose in several places, which could have easily been a show stopper! Luckily for me I was also able to make other repairs that were near impossible to do whilst sailing. So maybe I was meant to cross that out of bounds zone…!

Sitting like a floating duck for six hours, watching boats pass by had me vexed. By the time I had finished the penalty I was energised with the power of a bull ready to get back what I had lost. As the front two boats were now 40 miles ahead, and 4th place was virtually next to me within sight, I had to get out of there, and quickly. With the bit between my teeth I fought like mad over the next couple of days to make up the ground. After 36 hours I had overtaken Thibault the eventual winner, and soon recovered back into 1st place in front of Isabelle Josche, a Figaro sailor who I’ve raced against ever since my first transatlantic 11 years ago.

Soon the game changed and we were hit by more extreme weather near the Ice Gate, south of Newfoundland. Isabelle, Thibaut and I found ourselves reaching at high speed directly into a nasty steep sea which made the motion onboard absolutely appalling. It was an agonising time as I anxiously pushed hard almost waiting for something to break.

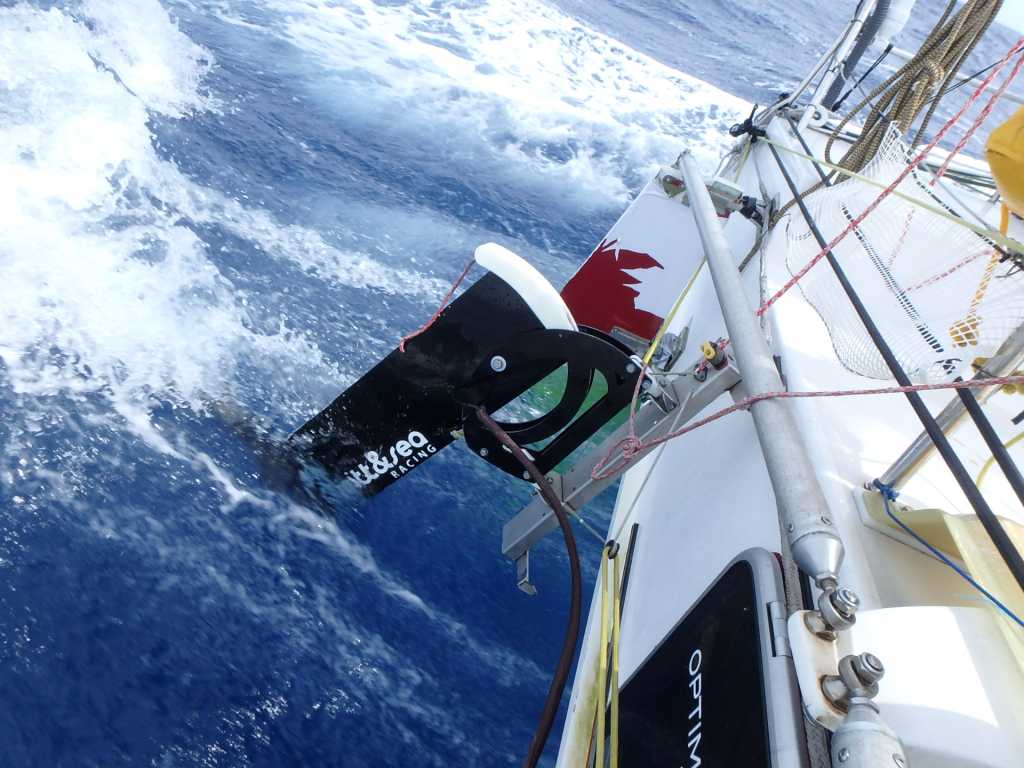

Soon I heard that Isabelle had taken on some serious structural damage, suffering a bulkhead failure and a crack in the side of the boat. Literally an hour later my jib deck furler completely exploded. This resulted in my foresail getting blown back into the rigging of the boat, significantly damaging the sail. I had to quickly recover, repair, and lash it directly to the deck to then rehoist it downwind. This cost me a lot of time, during which I was forced to give up my lead once again. It didn’t end there.

In fixing one problem I had created another. Through the repair I was forced to break the water integrity of the deck, which resulted in more and more water coming on board. I was having to bail frequently to stop the boat filling up as we pummelled through the waves. I found myself spending hours per day bailing rather than racing – having pools of water sloshing around the bow was not fast at all… To add to this drawback the jib then broke off the deck a second time, and I had to redo the lashing, losing yet another 10 miles to Thibault. This was a serious test of sanity as there is nothing more tortuous in losing ground on the opposition due to technical problems.

From this point on the whole race really took another turn and it became a damage limitation and problem solving exercise as it dawned on me that this was likely to be the quickest way to New York. Preserving the boat rather than racing it for maximum speed was the only option now. The final roadblock in the way that woke me up to this harsh reality were the two long days of brutal upwind gales that we had to get through before we could even think about having pancakes for breakfast in Manhattan.

When the gale hit, the wind was typically far more than forecast and whilst taking a 3rd reef in the mainsail the back of the sail flapped itself into pieces in minutes. To my horror it suddenly then ripped horizontally across almost the entire width of the sail. Evidentially the sail was not built for racing upwind across the North Atlantic, it had simply had enough.

This was a serious game-changer. With a damaged mainsail, it wouldn’t be possible to sail upwind, which was the fastest route to New York. I stopped the boat and spent several hours using all the repair material I had on board to effect a repair. However, the material was insufficient and on rehoisting the sail the repair works pulled away, pushing us back to square one. This was the low point in the race for me. I could hardly make four knots without the mainsail and all the boat could manage was to either sail north or south. This was not getting us any closer to New York, which lay due west!

Not only would we now be unable to fight for the lead, it looked like we’d struggle to get to the finish within the allowed time limit. Truly emotionally and physically drained I decided it was time to grab some sleep – I woke up with an idea. I lashed the broken part of the leach together and hoisted the damaged sail to see if it improved the speed. Amazingly the boat was faster with it up than without, even though it looked as through a pirate ship had shot the mainsail apart with a giant cannonball. It was then a question of whether it would hold together well enough for me to stagger to the finish in 3rd place.

As soon as I had managed to revert to a positive footing and get things back under control, I was hit the following afternoon by a bombshell of problems that threatened to stop me getting to New York, again. The mainsail tore itself completely in two. The only way of keeping it in place was to climb the mast to lash and hold it up. Working up the mast on this fix I had a big shock. I found the forestay had become detached from the deck and the pin holding it in place had jumped in the sea. The only spare on board was already used in a separate repair job in the furler, which had also decided to unfortunately jump over the side earlier on in the Atlantic when the drum failed. With serious danger of losing my mast, I rushed quickly to secure some halyards in place of the stay.

After sorting out these issues, power became my next main problem. A solo sailors worst nightmare is to lose power simply because this prevents an automated pilot steering system that allows you to sleep. If you can’t sleep, then really it’s game over.

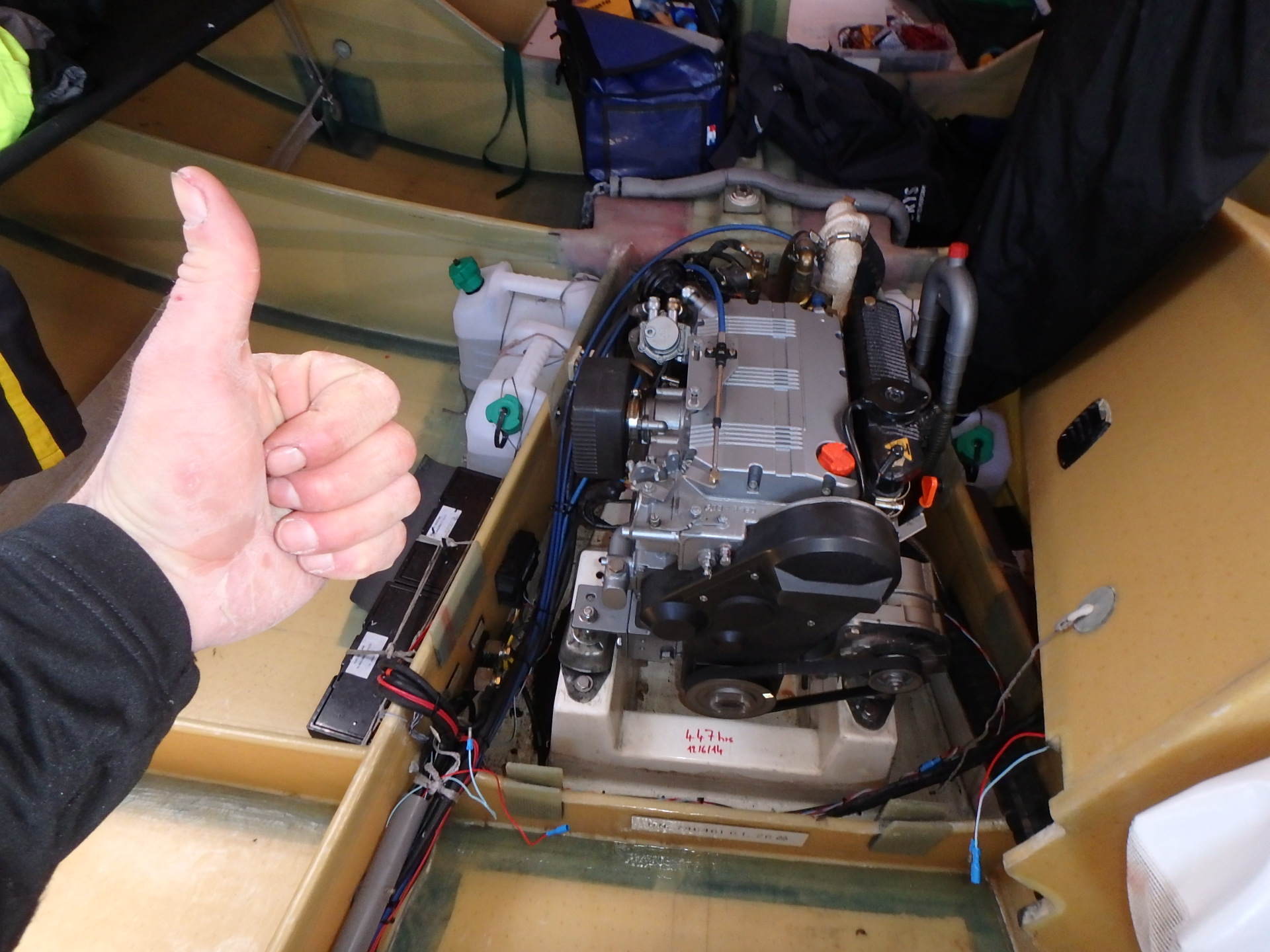

I had noticed that I was missing vital energy from the hydrogenerator, and went to check the back of the boat only to find that the frame had been smashed apart leaving the turbine hanging loose. I quickly went to start the generator – it ran for about two minutes top, before spluttering to a halt. This is really not what I needed at the last hurdle… There was only one thing to do, and that was to fix it, and quickly. I eventually traced it to a blocked fuel tank and rerouted the fuel feeder direct to a jerrycan. This time the engine ran for about four minutes before overheating. I couldn’t believe it, was I really jinxed in some way? Eventually I found that the engine was dry and that the water inlet was jammed, so I rerouted the inlet pipe instead to the water ballast tank. After a solid day of my head in the bilge, covered in diesel, eventually we had power… thank god!

Thankfully that was the end of the potential show stoppers to be thrown at us, and the last couple of days turned into some really enjoyable sailing. The waves subsided alongside the problems, and the wind went aft so I could hoist the gennaker and make some half decent speeds towards New York, whilst my mainsail flapped uselessly in the wind.

To finally reach the finish line and sail up to New York after nearly three weeks of such testing conditions was an incredible and unforgettable experience. I was surprised by family and friends and the representative for Imerys at the finish line, and we paraded Imerys up through the channel towards Manhattan. I felt very proud indeed to sail Imerys past the Statue of Liberty, completing the podium, after all the challenges and setbacks of the previous 19 days.

I guess that largely explains why I like taking on oceanic challenges, particularly single-handed. This race has redefined what I thought were my limits of mental and physical exhaustion, and it is incredible to look back on how many challenges I have managed to overcome in order to get this far. If anything it has given me a massive boost in my approach to problem solving. Serious dramas at the start of the race would now look like petty problems towards the end, and it has highlighted that despite lots of things getting in the way, there are always several ways round to reach a solution.

Last but by no means least, I want to stress just how much incredible support I had to enable me to take part in this unbelievable race and adventure, and to say a huge thank you to everyone involved. In particular I would like to thank our core partners; Imerys, Asset Leverage Consultants, Hotel du France, Bruichladdich, Carey Olsen, Jersey Marinas, and Hydrogenics. Without their invaluable support it would not have been possible to reach the start.

Would I do The Transat again? Absolutely.

Phil